BUSH'S "NEW

PEARL:"

NEGLIGENCE IN PREVENTING ATTACK?

"Al

Qaida's

expected

retaliation

for

the

U.S.

cruise

missile

attack

against

al

Qaida's

training

facilities

in

Afghanistan

on

August

20,

1998,

could

take

several

forms

of

terrorist

attack in the nation's capital. al

Qaida could detonate a Chechen-type building-buster bomb at a federal

building. Suicide bomber(s) belonging to al Qaida's Martyrdom Battalion

could crash-land an aircraft packed with high explosives (C-4 and

semtex) into the Pentagon, the headquarters of the Central Intelligence

Agency (CIA), or the White House.....

"If Iran's mullahs or Iraq's Saddam Hussein decide to use terrorists to

attack the continental United States, they would likely turn to Bin

Laden's al-Qaida. Al-Qaida is among the Islamic groups recruiting

increasingly skilled professionals, such as computer and communications

technicians, engineers, pharmacists, and physicists, as well as

Ukrainian chemists and biologists, Iraqi chemical weapons experts, and

others capable of helping to develop WMD. Al-Qaida poses the most

serious terrorist threat to U.S. security interests, for al-Qaida's

well-trained terrorists are actively engaged in a terrorist jihad

against U.S. interests worldwide."

-THE

SOCIOLOGY AND PSYCHOLOGY OF TERRORISM: WHO BECOMES A TERRORIST AND WHY? Report

prepared under an Interagency Agreement by the Federal Research

Division, Library of Congress, September 1999

The

legacy of "Pearl"

lives on more strongly than ever

after the suicide hijackings which surprised the world and killed

thousands on September 11, 2001.

These attacks raise long familiar issues about the nature of

intelligence and surprise. As in the case of Pearl Harbor, the

discussion of why the United States was caught napping may continue for

years.

In mid May 2002 major American news media reported that although

generalized warnings of Osama Bin Laden's plans to hijack American

airliners reached the White House just weeks before 9/11, no specific

warnings or preventative steps were taken. Opposition Democrat leaders

quickly seized upon the reports to push for an investigation.Skepticism

of official accounts, especially by families of 9/11 victims, led to

establishment of the 9/11 Commission by the President and Congress,

Novemeber 27, 2002. The Commission's full

report was issued on July 22, 2004.

Early press revelations suggested a pattern familiar in other

successful surprise attacks, including Pearl Harbor:

A)

Bureaucratic "filtering out" of

what in hindsight appear as compelling specific early warning signs.

B) Failure to analytically link reports scattered over time and

location by different intelligence groups, reports which, if pulled

together, might suggest "new" enemy tactics of surprise attack.

C) An overburdening of analysis by multiple clouds of what later

appeared to be misleading, inconsequential generalized warnings. This

sometimes leads to emphasis on protecting the wrong possible targets.

D) A tendency for high policy makers to demand specific information on

specific attack plans at specific times, rather than to take

precautions based on general intelligence, possibilities, and

probabilities. This demand for what may be impossible can hamstring

defensive preparations by federal, state or local authorities.

Patterns such as these can be reinforced by bureaucratic

disorganization, turf rivalries, and fragmented analyses left to gather

dust on shelves or in computer databases. There can be emotional and

intellectual "blind spots" at low, middle, or higher levels of

intelligence gathering and policy making. Such blind spots can be most

telling when multiple decisions and overwhelming emphasis on other

matters rule the day.

Only the work of future historians is likely to reveal what happened

before the September 11 attack. With an inexperienced new president and

a sometimes "out of control" intelligence bureaucracy, the results are

not in any way surprising.

Indeed it would have been a sharp break with the history of modern

intelligence and modern warfare if the attack of September 11 had been

successfully predicted and headed off by American intelligence and

policy makers.

(For an analysis of surprise and the 9/11 attack see "Strategic

Insight:

Surprise

and

Intelligence

Failure,"

by Douglas Porch and James J.Wirtz, Center for Contemporary Conflict

(CCC), the research arm of the National Security Affairs Department at

the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California.)

*******

The following revelations gradually reached the American public. They

are systematically dealt with in the July 22, 2004 report

of the 9/11 Commission.

Some were highlighted by a joint Congressional committee staff report

released September 18, 2002. It concluded the U.S. failed to act on

warnings in 1998 of a possible plane attack.

An August 1998 intelligence report from the Central Intelligence Agency

was just one of several warnings the United States received, but did

not seriously analyze, in the years leading up to the Sept. 11 attacks,

according to the study detailed at a Congressional hearing. The

existence of the 1998 intelligence report was disclosed in a

presentation by the committee's staff director, Eleanor Hill.

From 1998 to the summer of 2001, the C.I.A., the F.B.I. and other

agencies repeatedly received reports of al Qaeda's interest in

attacking Washington and New York, either with airplanes or other

means. The threat level grew so high that by December 1998, the

director of central intelligence, George J. Tenet, issued a

"declaration of war" on al Qaeda, in a memorandum circulated in the

intelligence community. Yet, Ms. Hill was quoted as saying, the

intelligence agencies failed to adequately follow up on the

declaration, and by Sept. 10, 2001, the F.B.I. still had only one

analyst assigned full time to al Qaeda.

The 1998 intelligence report about the trade center cited plans by a

group of unidentified Arabs, who the United States now believes had

ties to al Qaeda, to fly an explosives-laden plane from a foreign

country into the trade center. American intelligence officials were

quoted as saying that despite the similarities, they did not believe

that the 1998 report was related to the Sept. 11 attack.

While the joint committee made public several intelligence reports that

had been received in the years before Sept. 11 that related to al

Qaeda's intentions to launch an attack inside the United States and its

interest in using aircraft for terrorism, Ms. Hill emphasized that the

joint committee had still not found a "smoking gun" that could have

helped prevent the Sept. 11 attacks.

"People have said there was no smoking gun," Ms. Hill said. "But there

was still a lot out there that was never pulled together."

As with Pearl, "revisionist" interpretations of September 11 already

emerge. Critics

argued President Franklin Roosevelt knew of the coming attack and

allowed it to happen as a way of overcoming public opposition to

joining a war against Germany and Japan. As of this writing, there are

no serious accusations that Bush knew of the specific coming attack,

but rather that he ignored warning signs presented to him.

A parallel line of revisionism is likely to open. Some revisionists

with an isolationist bent argued Japan was "forced"

to attack at Pearl because President Roosevelt was moving aggressively

to use an oil embargo to force Japan out of China and block its its

plans for a Japan-dominated "co-prosperity zone" in Southeast Asia.

Some on the Left have begun to interpret the September 11 suicide

attack as a "preemptive strike" by Osama Bin Laden amid American plans

to launch a worldwide offensive against the al Qaeda network.

Unlike Pearl Harbor, the Twin Towers attack was aimed at civilians, not

military forces. The attack on the Pentagon was largely symbolic, with

no serious aim to knock out US military capacity. By contrast Japan's

December 7 attack was clearly targeted to disable American military

forces in the Pacific long enough for Japanese armies to conquer China

and Southeast Asia.

The Twin Towers attack was no doubt planned long before any final White

House decision to step up actions against Bin Laden. But the September

11 attacks were clearly an escalation of a deeply rooted conflict waged

between Bin Laden and the American government for many

years.

American plans to take a more aggressive approach toward Bin Laden's

terrorist network were suggested in a May 16, 2002 MSNBC report by

NBC's Jim Miklaszewski.

According to the report, which cited U.S. and foreign sources,

President Bush was expected to sign detailed plans for a worldwide war

against al Qaida two days before Sept. 11 but did not have the chance

before the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington.

The document, a formal National Security Presidential Directive,

amounted to a game plan to remove al Qaida from the face of the Earth,

one source was cited as saying.

The plan dealt with all aspects of a war against al Qaida, ranging from

diplomatic initiatives to military operations in Afghanistan, the

sources said on condition of anonymity.

In many respects, the directive, as described to NBC News, outlined

essentially the same war plan that the White House, the CIA and the

Pentagon put into action after the Sept. 11 attacks. The administration

most likely was able to respond so quickly to the attacks because it

simply had to pull the plans off the shelf, Miklaszewski reported.

*******

In

a detailed May 16, 2002 press briefing, as

reported in next day's The New York Times,

Condoleezza Rice, the president's national security adviser, said the

government had received numerous reports of terrorist threats in

summer, 2001. But she emphasized that the information seemed general

and pointed toward potential attacks overseas. In addition, Ms. Rice

said that the briefing Mr. Bush received from the C.I.A. on Aug. 6 did

not mention a July memorandum from an F.B.I. agent in Phoenix who had

warned that Middle Eastern men connected to Mr. Bin Laden might be

receiving flight training in the United States

According to reporting by Bob Woodward and Dan Eggen in the Washington

Post Staff, May 18, 2002, the top-secret briefing memo

presented to President Bush on Aug. 6 carried the headline, "Bin Laden

Determined to Strike in U.S.," and was primarily focused on recounting

al Qaeda's past efforts to attack and infiltrate the United States,

said the Post report, based on "senior administration officials."

The document, known as the "President's Daily Briefing," underscored

that Osama Bin Laden and his followers hoped to "bring the fight to

America," in part as retaliation for U.S. missile strikes on al Qaeda

camps in Afghanistan in 1998, according to "knowledgeable sources."

According to this account, Bush had specifically asked for an

intelligence analysis of possible al Qaeda attacks within the United

States, because most of the information presented to him over the

summer about al Qaeda focused on threats against U.S. targets overseas.

But one source was cited in the Post as saying the

White House was disappointed because the analysis lacked focus and did

not present fresh intelligence.

Philip Shenon reported May 18, 2002 in The New York Times

that law enforcement officials acknowledged that the F.B.I. never

ordered a comprehensive investigation of flight schools before Sept.

11, even as individual F.B.I. offices were gathering compelling

evidence about links between students trained at the schools and al

Qaeda.

Shenon

noted the Phoenix memorandum was not the

first warning that terrorists affiliated with al Qaeda had interest in

learning to fly. In his 1996 confession, a Pakistani terrorist, Abdul

Hakim Murad, said that he planned to use the training he received at

flight schools in the United States to fly a plane into C.I.A.

headquarters in Langley, Va., or another federal building.

According to Shenon, since at least the mid-1990's, law enforcement

officials have known that some terrorist organizations were considering

suicide attacks using commercial jets.

In 1994, French investigators have said, a group of Algerian hijackers

seized a Paris-bound Air France flight and planned to crash it into the

Eiffel Tower or blow it up over Paris. The plot was foiled when French

commandoes stormed the plane.

In 1995, Mr. Murad, the Pakistani pilot tied to Mr. Bin Laden, was

captured, and under interrogation by

Philippines intelligence officers working

with the F.B.I. and the C.I.A., American law enforcement officials

said, he confessed on video to his role in the plot to bomb airliners

over the Pacific.

The American officials said he also acknowledged he had planned to fly

a plane packed with explosives into the C.I.A. headquarters or another

federal building. Details of the plan had been shared with F.B.I.

headquarters by the middle of 1996.

Mr. Murad's plot was noted

in a September 1999 U.S. intelligence report suggesting that al Qaeda

might hijack an airliner with the intention of crashing it into the

Pentagon or another government building. The intelligence report, The

Sociology and Psychology of Terrorism: Who Becomes

a Terrorist and Why was

prepared

for

the

National

Intelligence

Council

by

the

Federal

Research

Division

of

the

Library

of

Congress.

It

was

widely

shared

within

the

government

and

has

long

been available to the public over the Internet.

(For an exercise in the ambiguities of intelligence analysis, pull up

the above voluminous

report

on the internet, search it on

subjects of airliner hijacking and suicide terrorism -- then evaluate

for yourself how compelling these "warnings" might have appeared AT THE

TIME. Next, to see how this report looks with the "benefit of

hindsight" examine a CBS TV news

report from May 17, 2002, '99 Report

Warned Of Suicide Hijacking.')

9/11 COMMISSION

REPORT: CALL FOR

REORGANIZATION

NEGLECTS HISTORY, CULTURE, MINDSET

Conclusions of the 585 page 9/11

Commission Report, released July 22, 2004,

largely dovetail with previous studies such as the Joint Congressional Report,

released July 21, 2003. New is the graphic, extremely readable quality.

The Commission strategy was to produce a report which would be so

widely read that enormous public pressure would build on the winner of

the November presidential election to consolidate and streamline

intelligence gathering and review. Critics have already argued such

reorganization to increase bureaucratic and political restrictions on

sound intelligence analysis and communication.

The Report proposed a Senate confirmed National Intelligence Director

within the office of the President. The leader of a proposed National

Counter terrorism Center (NCTC) beneath the intelligence director would

have deputy cabinet secretary rank.

Surprisingly the 9/11 Commission Report places almost no emphasis on an

understanding of history, culture, and mindset as a foundation for

intelligence analysis of leaders of other countries and movements.

There is no vigorous exploration of how politics and bureaucracy can

undermine intelligence analysis built on an understanding of history

and culture.

The 9/11 commission report devotes only eight of its 585 pages to

historical and cultural context (page 47 to 55). There is almost no

mention of American support for Israel, and is little explicit analysis

of Islamic extremism as in part a "reaction" to or "blowback" from

growing American power in the Mideast. Absent is any sustained analysis

of the cultural and historical interaction between the U.S. and the

Islamic world.

Here are some key points:

1)

In the months leading up to 9/11

Osama Bin Laden's major priority was to strike INSIDE the US -- not

outside. American policy makers understood in general terms that he

wanted to attack inside the US but because they had more specific

intelligence on his plans outside the US than inside the US, they

failed to see that his CENTRAL PLAN was a crippling attack inside the

U.S.

Lack of HARD intelligence of an attack inside the U.S. was interpreted

as meaning LOW PROBABILITY when it really meant American intelligence

had not penetrated Bin Laden's network, was unable to put together the

limited evidence and speculation at hand -- and just did not know what

was going on.

2) In the months leading up to 9/11 top officials focused mainly on the

possibility that OVERSEAS Bin Laden operatives would strike at OVERSEAS

American targets. They assumed that any attacks inside the US would be

carried out by Bin Laden sleeper cells ALREADY inside the US. Because

they were never shown compelling intelligence on ongoing infiltration,

upper level officials never focused on what was happening: OVERSEAS

operatives were slipping inside the U.S. largely unnoticed.

Fragmentation of American domestic intelligence prevented the emergence

of HARD evidence which might have gotten the ATTENTION of upper or

middle level policy makers.

Policy makers thus did not consistently pushed for intensive,

coordinated surveillance of infiltration into the US from outside,

which would have required a shakeup of domestic intelligence procedures

involving the FBI and the CIA.

.

3) While intelligence analysts had long speculated on hijackings which

used airliners as weapons against government buildings, busy upper and

middle levels of US government lacked the imagination, attention span,

or "space" to understand the significance of this speculation -

especially in light of absence of specific intelligence coordinated and

communicated to the top.

Speculation, without hard evidence, is often dismissed, partly because

upper level officials, confronted with all kinds of speculation, are

reluctant to make it the basis of policy. But once a THREAT is

emotionally and politically enshrined as valid, then speculation can

become the basis of policy -- as for example the frequent focus on

WORST CASE SCENARIOS during the Cold War.

THE

"INTRACTABILITY" OF STRATEGIC

SURPRISE

Even before the hijack attacks,

the "legacy of Pearl" was a major foundation for Bush Administration

proposals to build an antiballistic missile system and ditch the 1972

Treaty

on

the

Limitation

of

Anti-Ballistic

Missile

Systems.

(Review Clinton Administration ABM

policy.)

Bush Administration officials clearly understood the danger of

surprise, but they focused on sophisticated missile, space and

communication technologies, rather than on simpler tactics of

disruption open to clever, determined "low tech" adversaries.

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld had distributed Roberta Wohlstetter's

classic 1962 study, Pearl

Harbor:

Warning

and

Decisions. to members

of the House Armed Services Committee. One purpose: to gain support to

make defense against surprise attack a major

aim of American military planning.

The Wohlstetter study, with its classic forward

by Thomas C. Schelling, concludes that because of subjective human

factors surprise can occur despite and even because of vast amounts of

intelligence data. Its conclusions had a deep impact on some American

military planners at the height of the Cold War.

In his work Clausewitzian Friction and Future War

defense analyst Barry D. Watts has labeled the inherent difficulty of

predicting surprise attack the "intractability

of

strategic

surprise." (Download .pdf

version).

This analysis draws on concepts of "friction and fog of war" derived

from the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz to suggest why

attack so frequently comes as a surprise despite advances in

information technology.

Wohlstetter's study, influenced by Cold War concern that the Soviets

might repeat a "Pearl," has reemerged as a briefing paper for the new

century, even after the Soviet Union has gone.

Rumsfeld was only one of those who warned that planners must consider

new forms of possible surprise attack, such as those on sophisticated

computerized information systems which support transportation,

communications, finance, and utilities.

**********

In January 2001, just months before 9/11, Donald Rumsfeld released a

report by a commission he chaired dealing with the danger of a future Space

Pearl Harbor. A future surprise attack

could target, among other things, American civilian and military

communication systems based on satellite technology.

"We found that the US in general, the DOD (Department of Defense) and

the intelligence community, in particular, are not very well arranged

to meet the national security space needs of the 21st century," said

retired admiral David Jeremiah.

Jeremiah took over the chairmanship of the commission from Rumsfeld the

previous month when the latter was picked by President-elect George W.

Bush as his nominee to head the Pentagon.

He said the country was becoming increasingly vulnerable as it faces

growing needs for communication satellites for cell phones, Global

Positioning System equipment, spying and ground infrastructure.

The report gave no price tag for new technological systems, but the

cost of replacing obsolete military satellites over the next decade is

estimated at 50 billion dollars.

It cited several examples of vulnerability to attacks. In 1998, 80

percent of US pagers broke down because of a problem with the Galaxy IV

satellite. Early the previous year, the United States lost contact for

three hours with several satellites because of computer problems at its

ground stations.

"Increasingly, people like (suspected terrorist

mastermind) Osama Bin Laden may be able to acquire capabilities on

satellites" and will be able to threaten US ground stations, Jeremiah

added.

The commission said that while it appreciated "the sensitivity that

surrounds the notion of weapons in space for offensive or defensive

purposes," it believed the US president should "have an option to

deploy weapons in space to deter threats to and, if necessary, defend

against attacks on US interests."

**********

President Bush's choice

of Air Force Gen. Richard Myers as new chairman of the Joint Chiefs of

Staff had reflected this Administration's emphasis on high technology,

space, and cyber war. Gen. Myers, a former head of the Air Force's

space programs, had headed a major study of strategy commissioned by

Rumsfeld. One of his tasks was to be to balance the new hi-tech

concepts of war with more traditional missions.

The Gulf War and NATO operations in Kosovo had reinforced this emphasis

on high technology: the lesson that a critical part of future war may

be the battle to attack and defend satellite-based systems of command,

control, communications, and information (C3I).

Implicit in the planning for such surprise attacks was the question:

who is, or is likely to become America's new enemy? How much spending

for this is "prudent" -- or will all the talking and spending for

military preparations in space create a new, unnecessary arms race?

After September 11 many of these questions seemed academic. The nation

would have to place immediate emphasis in the short-term, at least, on

preparing for terrorism and biological warfare.

KOREA'S LESSON

All

this seems quite peaceful, a long way from China's massive "human wave"

attacks against American soldiers in Korea.

The intelligence failures of Pearl Harbor seemed quickly repeated when

the Truman Administration failed to anticipate, deter or detect North

Korea's coming invasion of

the South in 1950. (Check the

analysis of intelligence

failure relating

to the North Korean attack in James F. Schnabel, United

States Army in the Korean War; Policy and Direction: The First Year, Center of Military History, United

States Army.)

The Americans followed up with still another "intelligence failure"

when they failed to take seriously early enough China's many open

warnings it would directly intervene. (Check Schnabel's analysis of how Chinese intervention caught

the Americans off guard.)

For who would have thought the Chinese would dare to make war on

America as U.S. troops confidently swept to the Chinese border after

repulsing a North Korean invasion? Americans had the atomic bomb.

Surely no Chinese in his "right mind" would dare risk an American

nuclear attack!

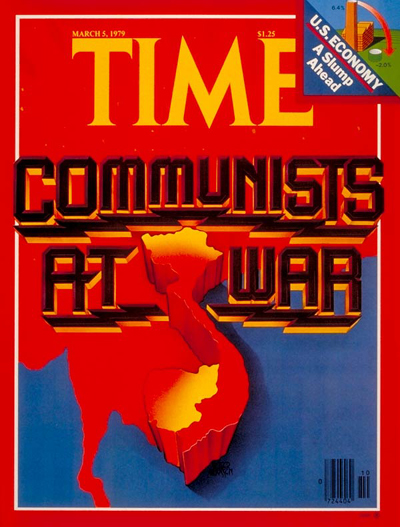

Then, as with Deng Xiaoping in 1979, China's leaders were determined

that "China must stand up."

Chinese like Deng were not in their "right minds." They gambled they

could face down American nuclear blackmail to demand China be treated

with respect. They issued a carefully escalating series of warnings

which American policy makers largely ignored. Whatever the cost, China

would stand up.

Beginning in October

1950, thousands of poorly armed, poorly trained Chinese young men went

to their deaths in attacks on the American soldiers marching across

North Korea to the Chinese border. The Americans reeled southward.

Thousands died on all sides in two years of wintry stalemate.

Nearly three decades later, in January of 1979, Deng Xiaoping and Jimmy

Carter consigned the Korean War legacy to history's dustbin by

establishing full diplomatic relations.

As they opened the door to peace, the brief but violent "Third

Indochina War" was about to erupt.